Responsibility is like a hot potato, but we have developed better ways to handle it than simply passing it on. We keep paying for this trickery, and so far, we can afford it. However, the stakes grow exponentially.

This is another essay in the Autonomy and Cohesion series. Autonomy and Cohesion is one of the essential balances that biological, social and socio-technical systems, basically everything from cells to cities, need to maintain to keep living.

Autonomy is the capacity to make uncoerced decisions, and cohesion is the action or fact of making a whole or working as a whole. Too little autonomy leads to ineffective, non-adaptive, and non-resilient systems. Weak cohesion results in inefficiency, and no cohesion means disintegration. Too much autonomy can cause silos, unreliable behavior, and various societal issues in markets. Excessive cohesion can lead to capacity problems and decision pathologies. Cohesion often requires the sacrifice of autonomy, but some technologies and practices can bring both cohesion and autonomy. The balance is relative and depends on culture, situations, and system type. The nature of the balance was discussed in more detail in the first and the second essays of the series.

Autonomy and agency are functions of freedom. Autonomy is the freedom to decide, and agency is the freedom to act. The freedom of objects can be quantified in degrees of freedom. It can be extrapolated, literally or metaphorically, to agents and naturally linked with independence and decoupling. The history of information technologies, from clay tablets to cryptocurrencies, shows an increase in decoupling. Content decoupled from medium, symbols from objects, books from authority, software from hardware, presentation from content, service from implementation, identity from host and so on. All these feasts of independence brought something valuable.

Decoupling is good, but only when a rigid coupling is replaced with a flexible one. In other words, when there is a balance between autonomy and cohesion (remember cohesion, in this context, subsumes coordination). Otherwise, decoupling can also be bad. Such is the case when we decouple a decision from its consequences and from a concrete individual who made the decision.

The Mastery of Hand-washing

Hand-washing took a long time to spread, and the recent pandemic showed that we are still bad at it. Symbolic hand-washing, on the other hand, is an ancient technique practised long before Pontius Pilate made it famous. Over the centuries, through regular practices and cultural innovations, we got remarkably good at it.

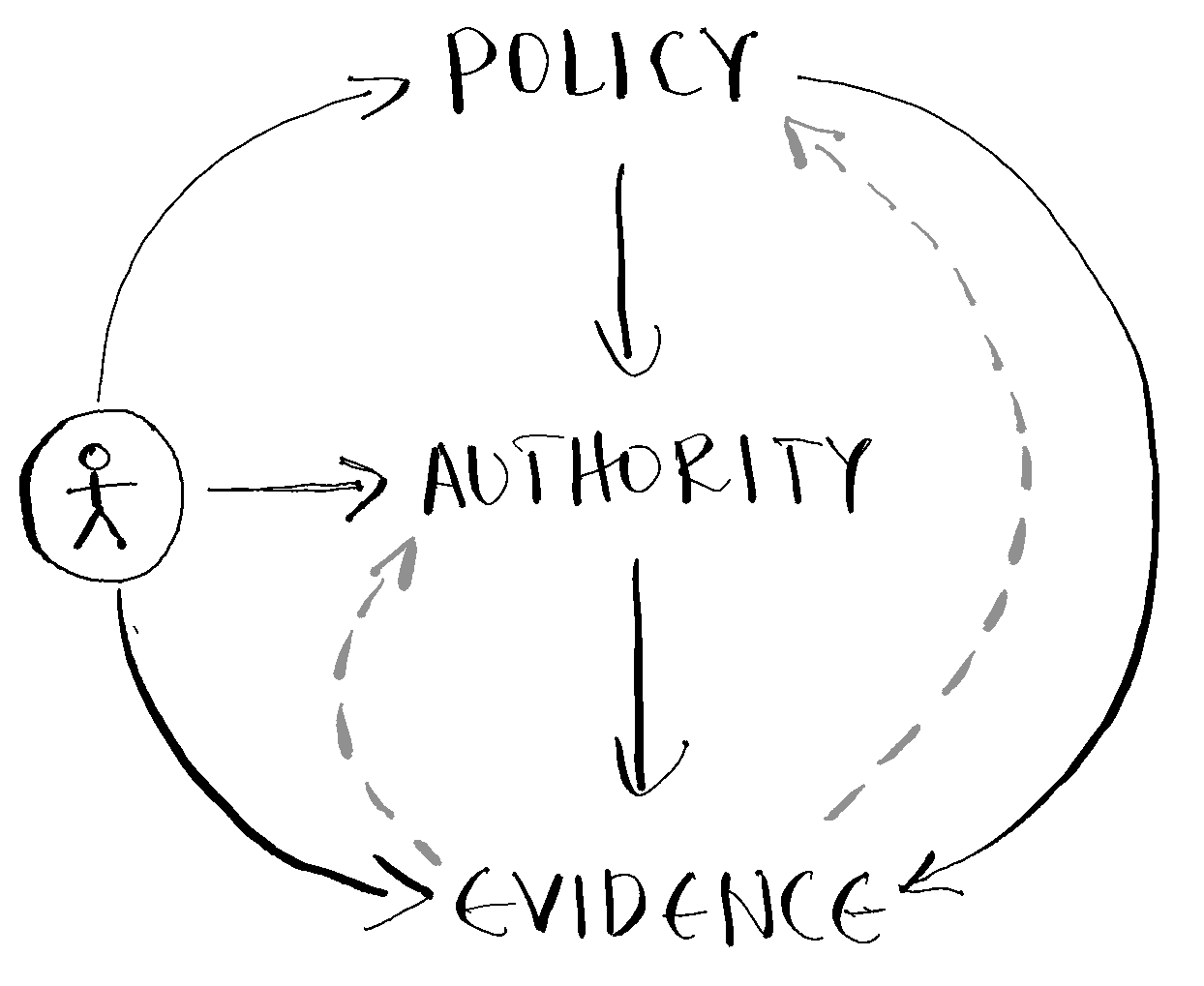

Today, the three most popular ways to avoid responsibility are to base a decision on policy, authority or evidence.

Policies

Policies are created by organizations. Organizations in their contemporary form are a recent invention, a few centuries old, and they are of a different nature than previous institutions. They are self-referential networks of decisions that reproduce themselves.1 Decisions are often based on specific rule packages called "policies." The creation of policies is one of the many ways organizations realize economies of scale. Policies reduce the effort spent on individual cases. However, in doing so, policies break two links. One is the link between a decision and an individual decision-maker, and the other is the possibility of those affected by the decision to influence the operations of the system.

describes this phenomenon brilliantly in The Unaccountability Machine.2 Fox News repeatedly accused a manufacturer of voting machines for rigging the 2020 US presidential elections, while both the executive and the journalists in Fox News knew that was false. Schiphol airport authorities threw 440 exotic squirrels in an industrial shredder because they lacked the necessary import papers. In both cases, nobody was accountable.There are policies of different qualities. It is believed that the best ones are those based on evidence. This is another fallacy3 that will become clear when we discuss evidence, but for now, it is important to realize that many decisions are attributed to policies that decouple any particular person from the responsibility of making the decision.

Authority

The second practice is the appeal to authority. Decisions with such bias are made by trusting the source of the information rather than evidence or sound reasoning. Companies make investment decisions based on reports from research agencies and suppliers with good reputations, and that often results in poor return on investment or an increase in their technical debt. Governments make authority-based decisions, bringing catastrophic results. Such decisions could lead to intervention causing a lot of damage by trusting high officials or intelligence sources (The Iraq War of 2003-2011) or not intervening on the basis of assurance of no risk given by financial experts, rating agencies and economists (The financial crisis of 2008).

Reference to authority is often chained. For example, a decision is based on a publication from a media or author with a high reputation, while the publication itself has an appeal to authority bias. The GoodlyLabs developed a tool to spot this and other biases in articles, but this just shows how widespread the problem is; not that much can be done about it.

Evidence

The third practice is grounding decisions in evidence. What could possibly be wrong with that? Not much if the decision-maker was basing her decision on personally verified evidence. But that’s not what happens in practice. There is an intermediary or a chain of intermediaries. Disguised, the appeal to authority sneaks in here again. And these cases are backed by an ingrained reverence for science.4 Yet, scientists are not immune to biases,5 and science is not an independently working machine. It is a social system intertwined in the society. It is tightly coupled with markets and governments, which brings perverse incentives and politics. In addition, there is a push in some cases to move from explanation to prediction, but science is not equipped to deal with complexity and uncertainty. It needs to reduce complexity by making hopefully relevant selections. Uncertainty has to be transformed into probability so science can apply its mathematical models. The result is decreased reproducibility and increased retraction. But even when all these issues are miraculously taken care of, what remains is the very basis of science, the claim for objectivity. And that claim is directly linked to responsibility.

Objectivity is a subject's delusion that observing can be done without him. Involving objectivity is abrogating responsibility – hence its popularity.

— Heinz von Foerster

The success of the objective method cannot be denied. But when it is forgotten that it’s only a method, it leaves blind spots. One such blind spot is human experience.6

Transferring responsibility to policy, authority, or evidence has also its thriving hybrids. One popular kind, aimed at or claimed, is evidence-based policy, the fallacy of which can be inferred from what I wrote already above and for the rest, you may check out The fallacy of evidence based policy paper that’s already in the footnotes. Another kind, let's call them evidence-authority hybrids, are scientific papers used as decision justifications that support their claims by citing highly cited other papers, where popularity and influence are taken for veracity.

The mastery of dealing with responsibility is well-evolved. Only occasionally does something blow up into a scandal, which may lead to improvements that, if not bringing long-term immunity, at least make the same kind of accident less likely. Yet, this mastery has not taken into account how the socio-technical systems grow and that they are reaching a limit.

In 1972, two important studies were published. One was the The Limits to Growth report, and the other was a paper called More is Different.7 In the years that followed, it was better understood in what ways more is different and what it is that is growing and reaching a limit. It turned out that it wasn’t just a growing population of individuals but of extended individuals whose technology extension is powerful in both cultural influence and energy consumption. I’ll go back to this, but before that, to see how it relates to the balance between autonomy and cohesion, we need to clarify its fractal nature.

Fractal of nested balances

All essential balances work at different levels of recursion. The focus of this series is on the balance between autonomy and cohesion. Let's trace this fractal of balances through a few examples.

Each cell in the human body is an autonomous self-producing system, creating its components, including its semi-permeable membrane that makes it possible for different elements to get in contact and produce the components that make up the cell. This, of course, costs energy, so the cell needs to get nutrients from outside and be able to produce energy and remove waste. In its operations, cells are autonomous, but this autonomy is balanced by coordination via signaling pathways and feedback mechanisms at different levels, resulting in a systemic response. At the next level of recursion, the autonomy of the immune and other systems is balanced by cohesion achieved via various coordination mechanisms. An example of coordination between the immune and endocrine systems is hormonal regulation, where the release of cortisol modulates the immune response to prevent excessive inflammation. Another mechanism preventing excessive inflammation, the inflammatory reflex, is again a matter of cohesion, this time between the immune and the nervous system. While this is something to read about but not directly observe, you can see the balance at yet another level by just using your hand. Your fingures have a high degree of freedom, but that is useful only when balanced with coordination for a simple action like lifting a glass to a complicated one like playing the piano.

In different societies, individuals' varying levels of autonomy are balanced by norms and laws.

In companies, the autonomy of employees to make decisions related to how they carry out their daily tasks is balanced by common goals, orders, reports, rules and policies. At every moment, the state of the balance can be different at different levels. For example, a team might have more autonomy than other teams, but at a lower level of recursion, it might work in a balanced state or unbalanced in the other direction by having a team leader who is a micro-manager.

Companies participate as autonomous agents in markets, making their own decisions based on market conditions, consumer preferences, and competitive strategies. Yet, this autonomy is constrained by market regulations, trade agreements, and economic policies.

While systems go in and out of balance at all levels at all times, the top global level, as far as human participation is concerned, has been out of balance for a long time with no signs of change. At any other level, we can find ways to restore the autonomy-cohesion balance or get away with responsibility-absorbing devices. At the global level, that won't work because of the way socio-technical systems grow and consume energy.

A Growing Population of Extended Individuals

Life is self-organizing. It created the conditions for its own existence.8 But for this self-organization to continue, it needs a constant supply of energy. This wouldn't be a problem if there were not three factors: growth, technology, and non-linear scaling. In the year More is Different, and The Limits to Growth were published, the Earth's population was 3.8 billion. Today, it is 8.1. It is quite sobering to look for a while at this live update, then at the chart below and back. Try it.

The chart shows the growth of the population of individual human beings. But we are not that anymore. We are extended individuals, and our technological niche consumes a hundred times more energy and grows faster. We have created an Anthropocene engine.

Individuals and the environment have interesting feedback relationships, and in any ecosystem, there are positive and negative. Every species would exponentially grow if you let them. But then there are regulatory interactions that prevent this. And then we realize that at some point, roughly 8,000-10,000 years ago, in our evolution, we have managed to close a positive feedback cycle between population, knowledge production and energy use. And that engine has been running ever since sometimes faster than others but genuinely accelerating.

— Manfred Laubichler9

The energy consumption of an individual human being per second is only 90 watts, but the actual consumption of the extended individual, that is, human + infrastructure supporting contemporary lifestyle, reaches in some places 11,000 watts and increases globally.10 While there are a lot of things now we can do to decrease the use of energy and increase the use of renewable energy, the speed of that transition, even not counting drawbacks based on technological (LLMs11) or political changes, is way too slow. It’s not likely that the shift and the rate of innovation will accelerate sufficiently since, as we saw above, autonomy and cohesion are out of balance at the global level. Freedom is not balanced with responsibility.

Luhmann, N., Baecker, D., & Barrett, R. (2018). Organization and decision. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108560672 (Original work published 1978)

Davies, D. (2024). The Unaccountability Machine: Why Big Systems Make Terrible Decisions - and How The World Lost its Mind. Profile Books. https://profilebooks.com/work/the-unaccountability-machine/

Saltelli, A., & Giampietro, M. (2017). The fallacy of evidence based policy. Futures, 91, 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2016.11.012

See The Scissors of Science for a sketch of some of the issues.

Commonly encountered biases in science include confirmation bias (favoring information that confirms hypothesis), funding bias (influenced by the interests of those funding the study), reporting bias (highlighting significant results and downplaying non-significant results), and citation bias, which is the appeal-to-authority manifestation in science. Another bias that has not received much attention so far is the elegance bias, which was exposed in Lost in Math.

Frank, A., Gleiser, M., & Thompson, E. (2024). The Blind Spot: Why Science Cannot Ignore Human Experience. The MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048804/the-blind-spot/

Anderson, P. W. (1972). More Is Different. Science, 177(4047), 393–396.

Lovelock, J. (2000). Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth (Subsequent edition). Oxford University Press. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/gaia-9780198784883

To get a better understanding of how scaling laws apply to the technosphere and the phenomenon of the Anthropocene engine, I strongly recommend listening to

’s conversation with Geoffrey West and Manfred Laubichler, where this quote was taken from.West, G. (2017). Scale: The Universal Laws of Growth, Innovation, Sustainability, and the Pace of Life in Organisms, Cities, Economies, and Companies (First Edition). Penguin Press. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/314049/scale-by-geoffrey-west/

See this interview from 2023 for a general idea of the energy consumption of ChatGPT and a study published earlier this month exploring energy consumption at different levels of application of LLMs.