Ruleful World

How pervasive constraints create cohesion and meaning

Rules rule our lives. Rules tell us on which side of the plate the fork must go and on which side of the road the car must go. Rules tell us where a bicycle must wait at a red light and where a plane must wait on the taxiway. Rules tell us which items count as hand luggage on a plane and which bottles count as a returnable deposit at the supermarket. Rules tell us how loudly we may speak in a library, and how loudly we may play music after 10 pm.

Rules define even their opposites. There is a general ordering that is the norm, and we can only communicate an alternative as deviating from it. To say external rules do not govern us, we say we are autonomous (self-law) or that we are privileged (private-law). Governance implies so strongly the notion of a ruler that an alternative form of governance, anarchy, can only be named in relation to it: “without ruler.”

This essay is part of the Autonomy and Cohesion series and the sub-series about rules.

Cohesion

Rules are a cohesion tool. They reduce interactional uncertainty. By constraining choices and making behaviour predictable, rules allow multiple autonomous agents to coordinate. We learn these qualities of rules from an early age. Make-believe play is random and boring without rules. Coming up with rules and strictly following them is what makes play fun until it exhausts their potential and begs for new rules.

Rules standardize practices (measurements, recipes, spelling, ways of moving) so people can rely on others’ behaviour and build higher-order institutions on top of that reliability. Rules vary in their flexibility and generality, but all perform the cohesion work of aligning expectations across contexts.

When cohesion is understood as both making a whole and working as a whole, two concrete dynamics matter most for rules to enable cohesion. First, rules compress the space of interactions, so coordination costs fall, and then coordination can scale. Second, rules create repeatable patterns that become objects of learning, audit and repair; they turn episodic agreements into durable protocols.

Determination

Rules restrict behavior, structure and meaning.

In traffic, stop at red, restricts motion. In dieting, fast for 12 hours restricts eating time. In boxing, do not hit below the belt restricts physical targeting. All these are restrictions on behavior.

A Haiku must have a 5-7-5 syllable structure. A password must contain at least one capital letter, a number, and a special symbol. A major chord must consist of a root, major third, and perfect fifth. All these are restrictions on structure.

A marathon winner is the one who crosses the finishing line first. A person under 18 is a Minor. An uncle is a parent’s brother. All these are restrictions on meaning.

But on closer examination, the rules restricting structure can easily be seen as restricting meaning. We define Haiku as a poem with a 5-7-5 syllable structure. An allowed-for-this-app password is one that contains at least one capital letter, a number, and a special symbol. A major chord is a chord consisting of a root, major third, and perfect fifth.

Rules may be all about restricting meaning, but they were historically unruly when restricting their own. Rules originated as construction instruments to ensure that columns were erected vertically, beams were straight, and angles were right. Then, after variation on correctness and measuring, their meaning shifted to model and paradigm, which nowadays, when rules are related to algorithms and regulations, seem rather strange.

We keep talking about “meaning” when discussing computational rules. But only humans are meaning-makers. If we bracket this intentionality, then all three kinds of restriction, on behaviour, structure and meaning, collapse into one, determination of a status.

Behavior rules determine the status of an action, for example, is the action permitted. Structure rules determine the status of a structure, for example, is a string well-formed. Meaning rules determine the status of a fact or entity, for example, is this person elected.

Determination is nothing more than a computed distinction, a distinction applied to itself. In the Rule of Saint Benedict, all rules can be changed at the discretion of the abbot. Discretion comes from discretio, drawing distinction. So both applying and bending rules is a matter of drawing a distinction. George Spencer-Brown was right, distinction is the perfect continence.

Computation

Nowadays, the formal expressions of rules looks like this:

Consequence ← Conditions.The left side follows when the right side holds. The left-pointing arrow can be read from left to right as “if.” Let’s take one of the earlier examples:

Uncle is a bother of a parent.Sounds like it was taken from a dictionary, and that’s not surprising. Rules restrict meaning. All definitions are rules.

A more formal expression will look like this:

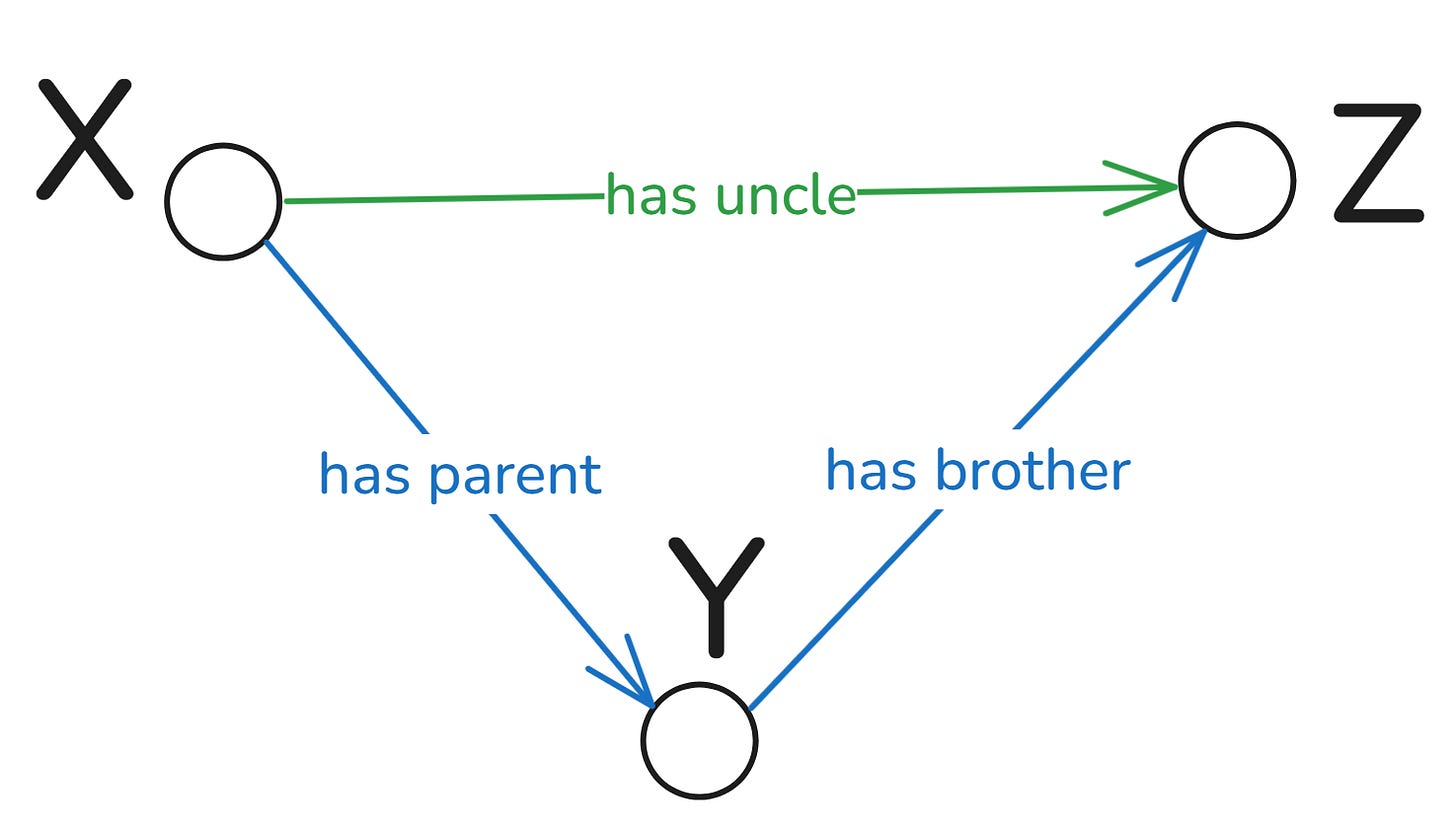

hasUncle(X, Z) :- hasParent(X, Y), hasBrother(Y, Z).The relationships link pairs of nodes: X to Y, Y to Z, and X to Z. The left-pointing arrow is replaced with:- but it can still be read as “if”. The comma is the logical and, meaning that both conditions on the right side must be true for the conclusion on the left to follow.

This rule is an algorithm to generate hasUncle relationships. If Mei has father Hao, then his brother Wei is her uncle. Replacing the variables X, Y, and Z with the constants Mei, Hai and Wei produces a new relationship, hasUncle, between Mei and Wei.

This rule defines the meaning of “uncle,” but it also illustrates the multiple meanings of the word “rule,” which historically shifted from straightedge to model to algorithm.

First, this rule is an algorithm, where the input of data into the conditions hasParent(X, Y), hasBrother(Y, Z), produces hasUncle relations between X and Z.

Second, this rule also serves as a template for producing such relationships. As such, it illustrates the lost meaning of rule-as-model, which Lorraine Daston is chasing in a big part of her book on the history of rules. That’s also true for rule-as-paradigm since paradigm comes from paradeigma (pattern, example).

And third, even the most ancient meaning of rule as straightedge can be illustrated, if we draw it.

Let’s look at this as a map. If you want to go from X to Z, it’s better to take the “has uncle” route than the “has parent...has brother” route. Via “has uncle,” you can go straight to Z. It is simpler and usually faster. And speed is one of the main reasons to use inference rules, as we’ll see in the next post.